Sovereignty after Slavery

Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti

J. Cameron Monroe

Abstract

This paper synthesizes recent archaeological research on the Kingdom of Haiti, a short-lived experiment in political sovereignty founded in the years following the Haitian Revolution. I will explore the potential for an archaeology of sovereignty in the Black Atlantic world. Examining both architectural spaces and artifacts recovered from the palace of Sans-Souci, royal residence of King Henry Christophe, this paper highlights a constellation of material practices that fostered an emerging ideology of authority in postrevolution Haiti. Collectively, this research is revealing how political agents drew creatively and strategically from both European material culture and Afro-Caribbean traditions in the practice of political authority in the Kingdom of Haiti, casting new light on the complex nature of sovereignty after slavery in the Age of Revolutions.

The archaeology of slavery in the Atlantic world has matured dramatically in recent decades, transforming from a provincial subset of historical archaeology in the American South to one yielding new perspectives on the formation of the colonial world and its enduring legacies (for reviews, see DeCorse [1999]; Fennell [2011]; Singleton [1995]). Research across the Caribbean, in particular, has played an important role in revealing the nature of everyday resistance, marronage, and consumer culture in post-emancipation societies with a view toward exploring how Africans and their descendants participated actively in the making of the modern world (Armstrong 2003; Armstrong and Fleishman 2003; Armstrong and Reitz 1990; Delle 1998; Delle, Hauser, and Armstrong 2011; Farnsworth 2001; Handler, Lange, and Riordan 1978; Hauser 2007, 2008; Kelly and Bérard 2014; Wilkie and Farnsworth 2005). The archaeology of slavery in the Atlantic world has thus matured significantly. Freedom and sovereignty emerge as central themes in this research agenda. And yet, one exceptionally relevant example has been absent from archaeological discourse, the independent states of postrevolution Haiti.

Haiti provides an unparalleled opportunity to explore the materiality of state making in the ashes of a colonial slave society, revealing the emergent tensions between Enlightenment political ideologies and the practice of political authority at the local level (Garraway 2012). This paper examines the materiality of political sovereignty on the Kingdom of Haiti (18071820), a short-lived experiment in nation building in the wake of the Haitian Revolution. Sovereignty in the Kingdom of Haiti gestured toward an ideology of universal liberty that gripped the Atlantic world and materialized in neoclassical architectural spaces and the consumption of particular European goods. Recent excavations at Sans-Souci, the palace of King Henry Christophe (first and last king of the Kingdom of Haiti), however, are documenting the evolution of Christophe’s architectural plan for the site over time, as well as the presence of material culture and foodways inspired by Afro-Caribbean traditions dating to an earlier period in the construction of Haitian sovereignty (1805-1810). Collectively, this research is revealing how political agents drew creatively and strategically from both European material culture and Afro-Caribbean traditions in the practice of political authority in the Kingdom of Haiti, casting new light on the complex nature of sovereignty after slavery in the Age of Revolutions.

Materializing Sovereignty in the Early Modern World

Recent anthropological approaches to sovereignty emerged in opposition to classical political theory, which exalted the sovereign state as imbued with singular absolute power within well-defined territorial boundaries and vertically rooted in the political apparatus of the state (Hobbes 1982 [1651]). Informed by insights from postcolonial and critical theory, as well as theories of globalization, anthropologists have in recent decades questioned the notion of the clearly defined sovereign territory, recognizing the complex and often overlapping claims to political sovereignty in modern states (Agamben 1998; Agnew 2018; Cattelino 2010; Geertz 2004; Li 2018; Rutherford 2012). Additionally, scholars have highlighted the often tenuous nature of the structures that enforce state power internally. Indeed, in recent anthropologies of the state, power has emerged as diffuse and multicentric (cf. Foucault 1980). Sovereign states, and the relationships of inequality that define them, have been recast as works in progress, ones that depend on political maneuvering by leaders and followers in innumerable public and private performative contexts (Rutherford 2012). Sovereignty emerges from this discussion as a political project that depends

fundamentally on establishing firm control over territories, building international affiliations and alliances, and advancing novel forms of status distinction among audiences of subjects.

Archaeological approaches to centralized states have experienced similar disillusionment with classical theories of sovereignty and increasingly emphasize the important role of material culture in the practice of sovereignty in the past. Central to these new archaeologies of sovereignty has been a focus on how material culture was deployed in public performative contexts to materialize social difference and status distinction (DeMarrais 2014; Dietler and Hayden 2001; Inomata 2006; Inomata and Coben 2006; Monroe 2014, 2010; Smith 2011, 2015). As a sphere of material practice that, by definition, both reflects and constrains human interactions, the importance of architectural space as a tool for shaping political struggle has been highlighted in recent archaeological research (Ashmore and Knapp 1999; Monroe and Ogundiran 2012; Pearson and Richards 1994; Smith 2003). This has resulted in spatial archaeologies of power that are transforming our understanding of how state agents extended their political reach across territories and how they sought to naturalize power among subjects, providing valuable new perspectives on the nature of politics in the past. In particular, scholars have argued that spatial strategies employed by elites can be geared both to monopolize the public experience of power (Ashmore 1989, 1991; Casey 1997; Fritz 1986; Helms 1999; Inomata 2006; Lefebvre 1991; Leone 1984; McAnany 2001; Monroe 2010, 2014; Thrift 2004) and to reorganize and routinize everyday social life (Bourdieu 1977, 1990, 2003; Donley-Reid 1990; Foucault 1995 [1977]; Giddens 1984; Monroe 2010; Moore 1996; Ortner 1984; Pearson and Richards 1994; Rabinow 2003). Buildings can emerge as powerful tools of domination, therefore, when they simultaneously broadcast elite perceptions of the world and shape popular experience of that world (Monroe 2014; Smith 2003).

And yet, archaeologists are equally concerned with the audiences such material displays of power were intended to impress, intimidate, and indoctrinate. Indeed, domestic settings were deeply embroiled in political practice and statemaking processes. Within quotidian contexts, archaeologists have identified the material traces of internal political jockeying (Blackmore 2014; Brumfiel 1992; Monroe and Janzen 2014), highlighted the important role of domestic labor in the operation of empire (Brumfiel 1991; Costin 1993; D’Altroy and Hastorf 2001; Hastorf 1991), and located evidence for the rejection or reformulation of dominant ideologies (BattleBaptiste 2011; Wilkie and Bartoy 2000). Some have identified situations where the production, use, and discard of domestic material culture unfolds in ways that suggest that social structures, writ architecturally, were in fact internalized, or at least closely emulated, by loyal subjects (Leone, Potter, and Shackel 1987; Monroe 2009; Pauketat 2001; Smith 2001). However, others have also questioned the degree to which architectural form and domestic material life always develop in lockstep, opening the door to considerations of archaeologies

of resistance, as well as acquiescence, to dominant political structures and ideologies (Battle-Baptiste 2011; Lightfoot, Martinez, and Schiff 1998; Mullins 1999; Wilkie and Bartoy 2000). Buildings, meals, and objects emerge in this discussion, as coconspirators in a political machine geared both to authorize and reject political sovereignty in the past (Smith 2015).

Archaeological research on the early modern world provides clear examples of the relationship between sovereignty, materiality, and audience in the past. Research in a range of colonial contexts has pointed toward the ways in which architecture was used in the service of political ideology in the early modern Atlantic world. Archaeologists, architects, and historians have argued that the spread of neoclassical architecture across Europe and its colonies in the eighteenth century was closely articulated with changing social and political values. This tradition, referred to as Palladianism after the sixteenth-century Italian architect Andrea Palladio, emphasized the use of “symmetrical compositions, temple-like house forms, geometrical spatial organization, motifs drawn from antiquity, use of the triumphal arch, and minimal ornamentation” (Singleton 2015:96) and gestured toward a deep and enduring past (Deetz 1996). James Deetz argued that neoclassical architecture publicly materialized an Enlightenment-era philosophy of individuality, social order, and universal freedom, what he called the Georgian worldview in Anglo-American contexts (Deetz 1996). Yet Palladian architectural norms simultaneously facilitated the expansion of technologies of social control and racial and economic inequality into the everyday lives of subjects, thereby serving the political interests of an emerging mercantile elite (Bailey 2018; Bentmann and Müller 1992; Deetz 1996; Dresser and Hann 2013; Leone 1984, 2005; Shackel, Mullins, and Warner 1998; Singleton 2015). Similarly, scholars have noted that architectures of order, symmetry, and control were deployed across a range of plantation landscapes, revealing how neoclassical principles of landscape design were used to monitor and control the everyday lives of enslaved colonial subjects (Armstrong and Reitz 1990; Bentmann and Müller 1992; Delle 1998, 1999; McKee 1992; Singleton 1990, 1999, 2015; Thomas 1998). Architectures of liberty and equality served, at differing social scales, to mask deepening inequalities defined in terms of race and class.

Importantly, archaeologists have explored the degree to which these patterns were associated with changes in material life in domestic contexts (Deetz 1996; Yentsch 1990, 1991). For example, Deetz noted that meals in the Georgian era were characterized by a decline of generalized stews in favor of the tripartite division of ingredients (meat, vegetable, and starch), characterized by a reduction in species diversity and standardization in preparation techniques (i.e., the use of saws to portion cuts of meat) (Deetz 1996:171). Additionally, Deetz noted a shift from a preponderance of communal serving vessels to individualized table services (cups, plates, saucers, and utensils) characterized by matching sets of pottery, reflecting the new ideologies of order and individualism gripping the

Atlantic world. These new preferences represent the emergence of a new consumer culture, in which material culture, architecture, and foodways allowed colonial subjects, emulating fashionable elites, to negotiate social status in a world in flux (Calvert 1994; Carson 1994, 1997; Leone 2005; Leone, Potter, and Shackel 1987; Martin 1994; Pogue 2001; Yentsch 1991).

This pattern contrasts starkly with that of plantation contexts associated with enslaved Africans in North America and the Caribbean. There, despite the imposition of European spatial norms in the planning and layout of plantation landscapes, enslaved Africans regularly rejected the domestic material correlates of this tradition (Ferguson 1992; Yentsch 1994). Indeed, rather than the highly segmented and individualistic meals and place settings desired by Europeans and EuroAmericans, enslaved Africans continued to prepare meals with irregularly chopped portions of meat, served in bowls and eaten communally (Deetz 1970; Ferguson 1992; Franklin 2001; Heinrich 2012; Kelly and Wallman 2014). Similarly, archaeology within the domestic spaces of the enslaved has identified spiritual practices that appear to have resisted the imposition of Euro-American cultural norms (Battle-Baptiste 2011; Franklin 2001; Heath and Bennett 2000; Samford 2007; Wilkie 1997). Interpreted in the context of the oppressive socio-spatial regime of slavery, such patterns can be read as evidence of the limitations of architectural regimes for transforming the domestic lives of enslaved subjects, an expression of agency in the context of an overwhelmingly hostile colonial structure.

Architecture and material culture were thus intimately entangled in new claims to power and authority, and their critique, in the emerging Atlantic world. Indeed, the spatial structure and historical symbolism associated with neoclassical architecture in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Atlantic world was deployed to send distinct signals to different audiences. On the one hand, neoclassical architecture can be read as the materialization of an ideology of individualism and liberty in keeping with Enlightenment political values. On the other hand, neoclassical spaces were built as technologies of social discipline and control designed to segregate and homogenize subjects according to race and class. In both cases, architecture masked deepening social inequalities and the expansion of state power. Domestic assemblages from historic sites, furthermore, reveal the degree to which such ideologies were internalized and accepted (or rejected) more broadly across communities of subjects (free and enslaved). The nature of these assemblages can be used, therefore, as an index of the degree to which people “bought into” the political values materialized by elites in buildings and landscapes, providing a quotidian counterpoint to the political narratives presented publicly.

Materializing Sovereignty in the Kingdom of Haiti

The Haitian Revolution ushered in an era of political change, one in which ex-slaves, maroons, and free gens de coleur united

to forge new political institutions in the ashes of Colonial Saint Domingue. Scholars have long struggled to appreciate the nature of political leadership in the decades immediately after this momentous event (Cole 1967; de Cauna 2004, 2012; Fick 1990; Geggus 1983; James 1938; Manigat 2007; Moran 1957). The Haitian Revolution has often been interpreted in the context of a universal history of political liberty, one based on the principles of freedom and equality espoused by the French Revolution (James 1938). Yet the various experiments in political order that followed were often autocratic in nature. Indeed, in subsequent decades, few political institutions were established to check centralized government authority, and the rural peasantry was essentially excluded from civic and political participation (Trouillot 1990). These factors reveal an emerging paradox between a discourse of political freedom and the practice of authoritarianism, in which Haitian rulers served simultaneously as liberators and subjugators of the rural peasantry (Garraway 2012).

The founding father of the first independent Haitian state, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, established the short-lived Empire of Haiti (1804-1806). His generals proclaimed him Emperor for Life, swearing “to obey blindly the laws that emanate from his authority, the only one that we recognize” (cited in Garraway [2012:4]). Following Dessalines’s assassination in 1806, Haiti was pulled apart by civil war, resulting in two states that experimented with divergent political models. In the southern half of the country, the Republic of Haiti (1807-) espoused the principles of representational democracy, maintaining both a senate and a relatively weak presidency (Dubois 2012:62), yet was structurally organized to benefit a wealthy mixed-race elite class. The political project initiated in northern Haiti by Henry Christophe, himself born a slave, provides an interesting contrast.

Immediately after the revolution, Christophe was appointed governor of the north under Dessalines. Following Dessalines’s assassination, Christophe declared himself president of the State of Haiti (1807), and in 1811 he proclaimed himself King Henry I of the Kingdom of Haiti, a hereditary monarchy founded on the principles of strong centralized government (Garraway 2012). Historians writing in the nineteenth century describe both the constructive and oppressive qualities of Christophe’s rule. Some describe him as a benevolent king driven by concern for the well-being of his followers (Madiou 1989), whereas others describe him as a despot bent on authoritarian rule (Ardouin 1858). His kingdom came to ruin in 1820, however, the culmination of enduring conflicts with the southern republic, the imposition of an economic embargo by a host of foreign nations, and, ultimately, his suicide.

Christophe instituted a broad set of political reforms across his territory, forging a stable state bureaucracy and a powerful military, invigorating rural production, and establishing formal economic ties with contemporary nation-states around the Atlantic. The polity was divided into three administrative divisions and six districts, and state officials managed and monitored rural agriculture within each zone (Roux 1816).

Across the kingdom, the “Code Henry” enforced a severe labor regime that sought to intensify the productivity of a struggling rural peasantry, and thus bore certain similarities with the colonial plantation society that it supplanted (Cole 1967). As a result, agricultural production soared, and the kingdom was annually exporting 15,000,000 pounds of sugar, 20,000,000 pounds of coffee, 5,000,000 pounds of cacao, and 4,000,000 pounds of cotton (Moran 1957:131). Despite the imposition of numerous embargoes against Haiti in the first decades of the nineteenth century, trade continued. By 1811, the kingdom had imported £1,500,000 in British goods (Cheesman 2007:194), and according to one account, 10 English, 43 American, 10 Danish, and 8 merchant vessels of various origins visited her shores in 1817 (Vastey 1923:cvii). The success of Christophe’s state depended in no small part on his ability to establish political authority across his realm, stimulate production and trade, and normalize economic relationships with contemporary states around the Atlantic world.

The success of this project also depended on the use of royalist symbolism to underwrite his political authority. Christophe established a Haitian peerage system based on the feudal European example, complete with heraldic crests and mottoes (Cheesman 2007:131; Moran 1957). Membership granted land and title to counts, dukes, and barons, each of whom was charged with managing administrative sectors and regions. Additionally, he promulgated symbolic associations with contemporary West African states, such as Dahomey. He maintained a standing army called the Royal Dahomets, who served as his political enforcers across the realm (Dubois 2012:62), as well as the Society of Amazons, a corps of women who accompanied the king and queen on royal processions (Dubois 2012:62). Both institutions drew inspiration from military institutions in the West African Kingdom of Dahomey (Alpern 1998), as did a number of fortresses bearing its name across Christophe’s realm (Madiou 1989:300). John Thornton (1993) argues convincingly that Christophe utilized such symbols of power to appeal to an essentially African rural population most familiar with monarchical forms of government. Doris Garraway (2012) argues that such symbols of state were used to make transnational claims about African equality and achievement, which was a central trope of Haitian revolutionary politics. Collectively, these tactics can be read as part of a complimentary set of royal strategies to establish regional hegemony across his realm, assert status distinction at the local level, and insert Haiti into the global community of nations on equal footing, the key elements of sovereign state making outlined above.

This experiment in Haitian sovereignty was intimately connected to material statements of power and authority (Trouillot 1995). Henry Christophe was an avid builder, earning him the popular nickname le roi batisseur (the Builder King). Christophe constructed nine royal palaces and 15 fortresses (including the massive Citadelle Laferrière), and reclaimed and renovated 15 prerevolution plantations as rural seats of power (Ardouin 1858:447; de Cauna 1990). Christophe’s architectural

efforts are most clearly visible today in the town of Milot. Milot’s occupation reached into the colonial era, and yet it transformed dramatically during Christophe’s regime. Habitation Milot appears on the Phelippeau map of 1786 and was described by the German geographer Karl Ritter as a “simple plantation” at this time (Ritter 1836:78). According to Ardouin, Christophe stationed military regiments there in 1802 (Ardouin 1858, vol. 8:369, 458), and it became his base of military operations until independence in 1804. By 1806 Milot was “a small town” and “the spot which has been selected by the general in chief [Christophe] for his country retreat” (Raguet 1811:409). Ritter suggests that at its height, the town boasted 160 houses and 500 residents, including the Haitian nobility who resided at Milot when Christophe’s court was in residence (Ritter 1836:78).

The expansion of settlement at Milot was closely linked to construction activities at Sans-Souci (fig. 1), Christophe’s largest palace and seat of power. This royal complex covered approximately 13 hectares, and according to Brown, during its construction “Hills were levelled with the plain, deep ravines were filled up, and roads and passages were opened” (Brown 1837:187). The complex contained numerous additional buildings: individual residences for Christophe, the queen, and the heir apparent; a military garrison for his Royal Dahomets, residences for state officials, and two extensive gardens. The ground plan and façade of the main palace reveal strict adherence to aforementioned neoclassical principles of separation, bilateral symmetry, the control of movement through space, and the use of Greco-Roman elements. These elements earned Sans-Souci “the reputation of having been one of the most magnificent edifices of the West Indies” (Brown 1837:186), described as a veritable Versailles in the Caribbean because of its splendor.

Vergniaud Leconte attributes the design and building of the palace to the architect Chéri Warloppe (Leconte 1931:273), yet there is significant disagreement on the construction history of the palace complex as a whole (see Bailey [2017] for a full discussion of the evidence). Off-cited oral traditions claim the palace was built rapidly between 1811 and 1813 (Bailey 2017:75), early in the reign of Christophe as king. However, its construction chronology was more complicated. The account of Norbert Thoret, eyewitness to the revolution and its aftermath, indicates that Christophe had already built a “superb home” for himself at Habitation Milot by 1804 (Nouët, Nicollier, and Nicollier 2013:47). Twentieth-century historian Vergniaud Leconte suggests that this building was located on the site later referred to as the palais de la reine (Leconte 1931:338). Christophe’s Gazette Officielle (no. 4, 1809), furthermore, reports that two years into his presidency (1809), he was already residing at his “new” palace at Sans-Souci, suggesting the possibility that this structure and the palais de la reine, visible today, were one and the same. The date of completion for the remainder of the complex is also somewhat ambiguous. Leconte indicates that the palace was finished in 1813 (Leconte 1931:349), two years into Christophe’s reign as

Figure 1. Aerial view of the main palace building at Sans-Souci looking southeast.

king. However, Karl Ritter, who visited the site during and after Christophe’s reign, claims it was not completed until 1817 (Ritter 1836:17). Whether or not final completions were made by this later date or the palace underwent subsequent renovations, the palace was clearly occupied and regularly used for public events in the early years of Christophe’s reign.

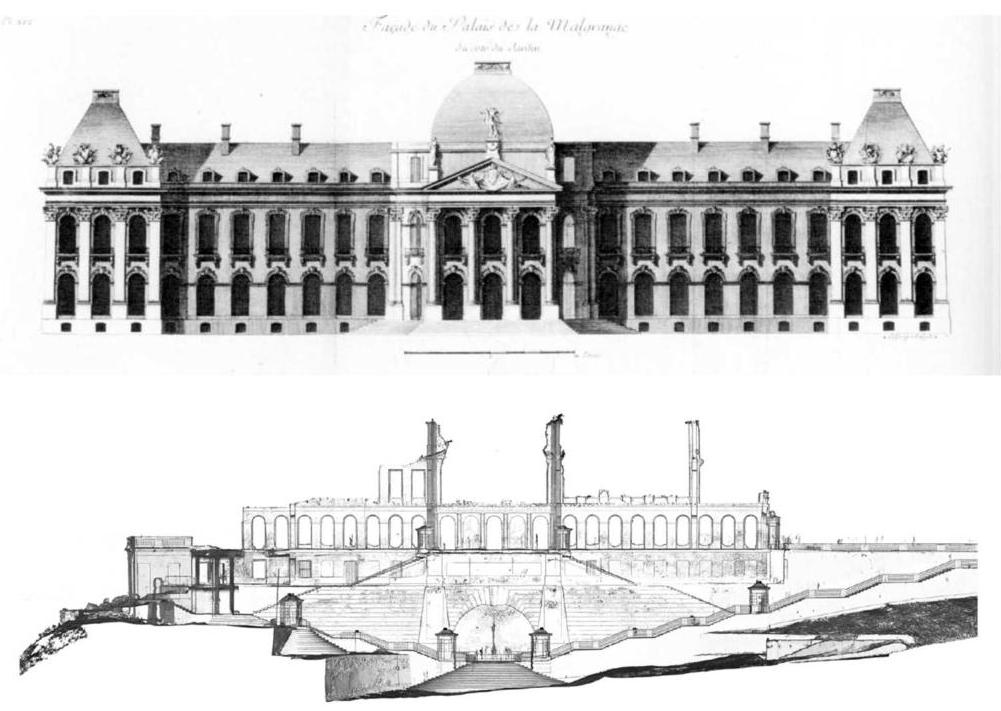

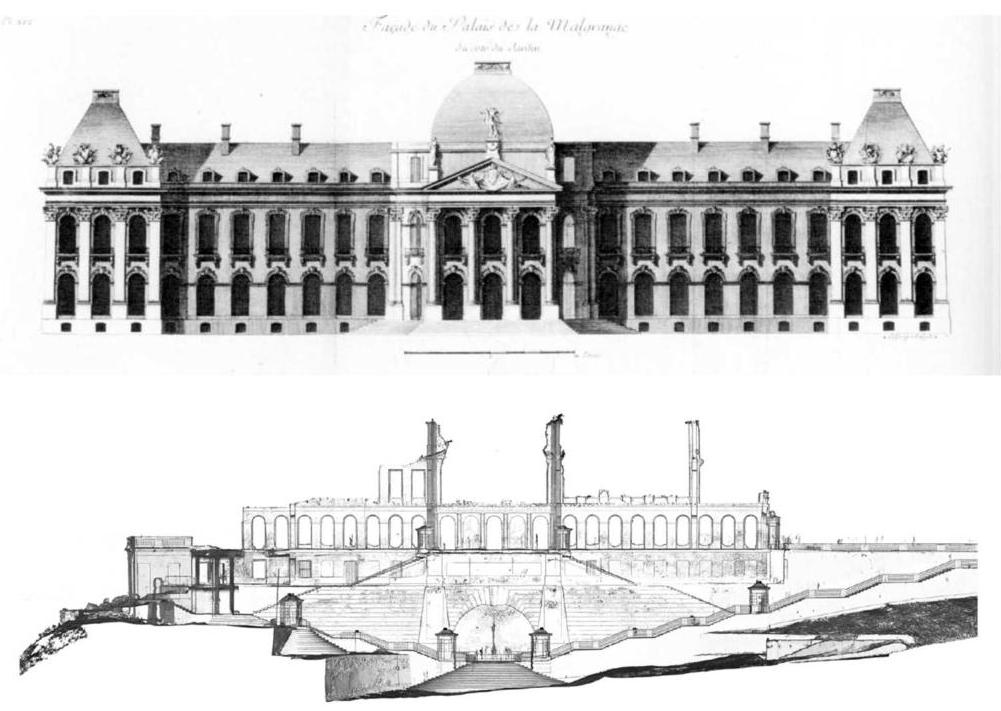

In the first published architectural analysis of the site, architectural historian Gauvin Bailey describes Sans-Souci as an example of “restrained Baroque Classicism of the Regency and Louis XV’s reigns,” and identifies Germain Boffrand’s Palais de la Malgrange in Lorrain as its probable inspiration (Bailey 2017:117) (fig. 2). Bailey highlights the use of the Doric order and monumental staircases on the front and back sides of the palace, representing an architecture of impact and power. Also of interest is the neoclassical formalism of Christophe’s garden, marked by multiple terraces, a central fountain, and royal bath, features that characterized garden landscapes around the Atlantic world in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (Cosgrove 1993; Leone 1984:383). However, while the design of the palace and outbuildings adhered to neoclassical formalism, absent is the strict adherence to Cartesian planning and golden ratios across the royal complex as a whole (Brinchmann et al. 1985). Sans-Souci gestured, therefore, to the architectural aesthetics of power that gripped the Atlantic world in this period, yet its planners forwent the kind of visual impact fostered by rigid Palladian rules of perspective applied to landscape design, in favor of an architectural landscape loyal to the natural topography.

Yet just as the architectural assemblage projected salient reminders that Haiti had entered the modern community of nations, the objects that animated material life at Sans-Souci palace did the same work on a smaller scale. Visiting the palace eight days after Christophe’s death, the collapse of the kingdom, and the ransacking of the royal palace, Karl Ritter described the scattered vestiges of its material assemblage:

The whole first floor contained a great many halls, richly decorated according to European taste. We were astonished at the devastation here. Not infrequently, we had to step over beautiful draperies or debris from mirrors. The furniture was made of mahogany wood, the windows covered with silk curtains and the floors polished. I saw glass windows here for the first time in this country, I even encountered a few glass paintings [Glasmalereien] in the apartments. (Ritter [1836:77-79], cited and translated in Bailey [2017:88-89], emphasis added)

Thus, material culture, and specifically “European taste” in material culture, played an important role in accentuating the grandeur of the royal court.

A taste for British material culture is particularly well attested at Sans-Souci. Portraits of the royal family were commissioned by English artists, and the well-known Richard Evans painting depicts Christophe in English Regency style dress (Bailey 2017:27). Sets of fine pottery emblazoned with the royal sigil were ordered from the Spode potteries in England. One newspaper account from 1811, published in the Evening

Figure 2. Above, Garden façade Germaine Boffrand’s Palais de la Malgrange (1712-1715) (from Boffrand, Livre d’architecture). Below, Elevation of Sans-Souci palace façade generated using terrestrial LiDAR (3-D scanning).

Mail, describes an extraordinary shipment of royal regalia destined for Christophe’s court that was confiscated by British customs for underrepresenting its total value:

Seizure of Christophe’s Regalia

The seizure made at the Custom house some time ago, of the valuable articles intended for the Emperor of Hayti, excited much curiosity. A list of them has been made out, of which the following is a copy:

- A Crown, set with Diamonds, Rubies, and Emeralds.

- A Case Containing two Breast-plates, and a pair of Drop Earings, set with Diamonds and Emeralds.

- A Case, containing a gold Cup.

- A Ditto, containing a Gold Salver.

- A Ditto, containing Diamonds and Rubies.

- One small Gold Fillagree Stand, set with Amethysts.

- One pair of Gold Spurs.

- A Gold and Silver Plume, set with Rubies, Amethysts, and Topazes.

- One small Gold Crown.

- One Row of Gold Beads and Tassels.

- One Diamond Collar.

- One Row of Pebble Beads and Crucifix.

- One Chrystal, with Tassel, and Relic.

- One Box containing sundry Diamond and Gold Pins, Brooches, Earrings, Crosses, and Watches.

- Seven Diamond Tiaras.

17, 18, 19, and 20. Diamond Lockets, Pins, and Rings. (Evening Mail, Friday, December 13, 1811)

The desire for goods such as these reveals their importance for establishing a sense of status distinction and international engagement in postrevolutionary Haiti (Cole 1967; McIntosh and Pierrot 2017). However, McIntosh and Pierrot (2017), citing advertisements in British newspapers that publicized Haitian orders of British goods, have gone so far as to argue that the conspicuous consumption of English material culture, specifically, was part of an ingenious public relations campaign to gain English popular support for Haitian claims to sovereignty. Thus material culture was also implicated in attempts to gain recognition and support at the international level.

The adoption of neoclassical architectural motifs and imported material culture is particularly significant for understanding how things were complicit in assertions of Haitian sovereignty in the era of Haitian monarchy. In buying into this assemblage of material symbols, Henry Christophe and his court adopted the material language of power in Europe and its colonies, making simultaneous claims to independence and equality at the international level, yet asserting royal power and authority within his nascent state. And yet our understanding of the development of this suite of material practices is poorly documented in the historical archive, as is our appreciation of the degree to which this ideology permeated the domestic sphere. Archaeological research, discussed below, is beginning to fill the gaps in our understanding of these processes, revealing how European material culture and AfroCaribbean traditions were assembled in elite domestic spaces in the years between the revolution and the crowning of Haiti’s second monarch.

Archaeological Research at Sans-Souci

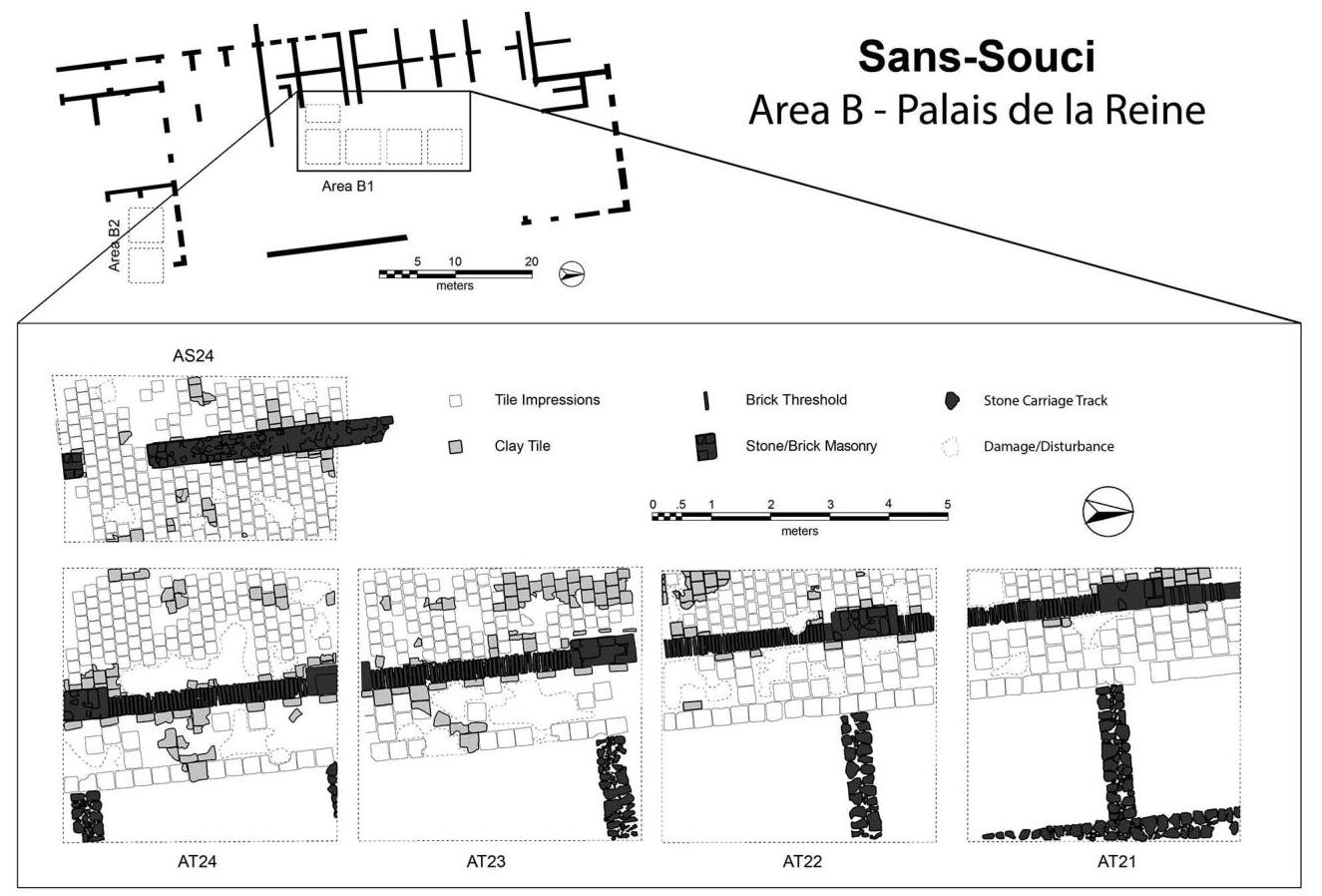

In the early 1980s the Haitian institution ISPAN (l’Institut Sauvegarde du Patromoine National) and UNESCO conducted an exhaustive architectural survey at Sans-Souci in preparation for its inscription as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, documenting nine major zones of visible architectural remains dating to the royal period (fig. 3). Archaeological analysis of these structures hinted at dramatic change over time, suggesting that Sans-Souci was the product of at least two major building episodes. Preliminary archaeological testing by ISPAN in the 1980s targeted the cour caimitier, a long platform that extends east to west across the palace landscape, reaching the main royal palace to the east, and the palais des ministres, a long multiroom structure aligned along the southern edge of the cour caimitier (fig. 3). ISPAN’s excavations in the palais des ministres identified the walls of a second multiroomed structure and associated staircase, hereafter referred to as the early phase building (EPB), below the final phase of construction (fig. 4). This structure extended under the cour caimitier and appeared to have been built in alignment with the palais de la reine to the northwest, suggesting that they were both part of a unified plan for the site that predated the royal phase of construction.

In 2015 the Milot Archaeological Project, a collaborative research project initiated by the University of California, Santa Cruz, the Bureau National d’Ethnologie (BNE), the Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien (MUPANAH), and the Institut Sauvegarde du Patromoine National (ISPAN), renewed archaeological surveys and excavations at Sans-Souci. These excavations were geared toward exploring the building chronology of the site and teasing out whether the visible structures were constructed as part of a unified plan or, rather, represented organic growth over time. Additionally, we sought to recover a sample of domestic material culture from each identified architectural phase that could inform on material consumption practices at Sans-Souci over time. This research targeted two areas of the site: the palais des ministres (area A) and the palais de la reine (area B) (fig. 3). Overall, these excavations confirmed three phases of settlement below the royal era structures. These include (1) a contact period Taino settlement, (2) an early postrevolution occupation, and (3) an architectural phase dating to the early years of Christophe’s rule. The following discussion will outline the architectural chronology of the site revealed by excavation and evidence for material consumption practices behind palace walls, highlighting how archaeological research is contributing to our

Figure 3. Plan of Sans-Souci, derived from terrestrial LiDAR (3-D scanning).

Figure 4. Excavations in the cour caimitier and palais des ministres initiated by ISPAN in the 1980s. Top, Plan of the area investigated with excavation units identified. Middle, Excavation unit profiles from units 12a and 12c in the Cour Caimitier documenting deep construction fill. Bottom, Plan of the Palais des Ministres revealing an earlier architectural phase below.

understanding of Haitian state making in the early nineteenth century.

Architectural Chronology

In 2015, 2017, and 2018, we reopened ISPAN’s excavations in five rooms in the palais des ministres (designated area A): rooms 1,2,3,10, and 11 . In rooms 1,2 , and 3 (area A1) (fig. 5), ISPAN’s excavations were geared toward tracing wall foundations alone, and thus substantial sections of stratified material were left intact. Excavations within this material were initiated at the floor level of the latest phase of construction, revealing a complex stratigraphic sequence including multiple phases of construction and occupation. Just below the floor levels of all three rooms, we identified layers of stone, brick, and mortar construction fill, which was deposited on a simple mortar floor (F27) that reached the walls of the EPB. Below this floor, we identified stratified layers of artifact-rich domestic

midden more than a meter thick. This material passed under the foundations of the EPB and thus predated it, and contained sherds of shell-edged pearlware with scalloped edges and impressed straight lines. Production for this style of pearlware ranges from 1805 to 1830, providing a terminus post quem of 1805 (Miller and Hunter 1990). This midden thus postdates the revolution and corresponds to the years before large-scale construction began (represented by the EPB) at Sans-Souci. At the bottom of this midden, we identified a small stone cobble wall extending across rooms 1 and 2 (W45), over which the southern wall (W5) of the EPB was built. This midden bottomed out on a layer of silty sand devoid of artifacts. 1 Excavations

- It is also worth noting that in 2017 our excavations in room 1 continued below the level of what we thought was sterile sand. These excavations revealed a second midden containing iron fragments, cattle bones, and indigenous meillacoide pottery of the ninth to the sixteenth centuries. This material denotes the presence of an indigenous settlement

Figure 5. Views of MAP (Milot Archaeological Project) excavations in the Palais des Ministres, area A1. Top, View of Early Phase Building (EPB) under rooms 2 and 3 of the Palais des Ministres taken from the southeast. Bottom, View of the walkway running parallel to the EPB under room 3 of the Palais des Ministres taken from the south.

in 2018 revealed a stone retaining wall and mortar-surfaced walkway south of and running parallel to the EPB.

Our excavations in area A1, therefore, reveal that the EPB and its associated walkway were constructed on top of a dump of midden material deposited after 1805. This linear arrangement of room cells, flanked by a long walkway on the south, is thus architecturally analogous to the palais des ministres constructed above, suggesting these later buildings were simply a modified version of an existing plan. We are not yet able to determine decisively whether the EPB dates to the periods of Christophe’s presidency (1807-1810) or his reign as king (1807-1820). Because historical sources suggest that the initiation of large-scale building and landscape transformation only began in 1810, a year before Christophe was crowned, it is likely that the EPB dates to this period. This sequence would put the date of the midden below to between 1805 and 1810, or the early years of political consolidation after the revolution.

with a terminal phase of occupation dating to the contact period. Unfortunately, this material was encountered on the last day of excavation in 2017 and was sealed and backfilled for future excavation.

In 2018, furthermore, we reopened ISPAN’s excavations in rooms 10 and 11 (designated area A2), where we identified additional analogous architectural sequence (fig. 6). ISPAN’s excavations in the 1980s revealed a stone wall and staircase in each room. Our work here in 2018 was devoted to cleaning off post-excavation erosion and accumulated modern trash and excavating undisturbed material associated with these features. Once cleared, we identified a similar stratigraphic sequence to that identified in area A1. In room 10, for example, we identified a mortar floor associated with the final phase of construction in the palais des ministres. This floor sealed almost a meter of construction debris that, in turn, capped an earlier retaining wall of a plaster-paved terrace extending north, under the cour caimitier and east into room 11. In room 11, furthermore, we were able to determine that the staircase in room 11 was slightly curved and rose from east to west, reaching the terrace identified in room 10.

Like the architectural features in area A1 to the west, these structures appear to have served as precedents for the final phase of construction at Sans-Souci. For example, the stairway leading up to the mortar-paved surface in rooms 10 and 11 finds a convenient analogy in the southern entrance to the palace itself, though on a dramatically smaller scale. Additionally, the angle of intersection produced by the walls of the two early-phase structures in areas A1 and A2 (153 ∘) is similar to that produced by the later palais des ministres and the southern façade of the royal palace (163∘). This suggests that the staircase identified may have led to an earlier palace building on site, which was covered over during the construction of the cour caimitier. The final, royal phase of construction thus expanded on a general plan and principles of design that were already well established at Sans-Souci as early as the beginning of Christophe’s presidency.

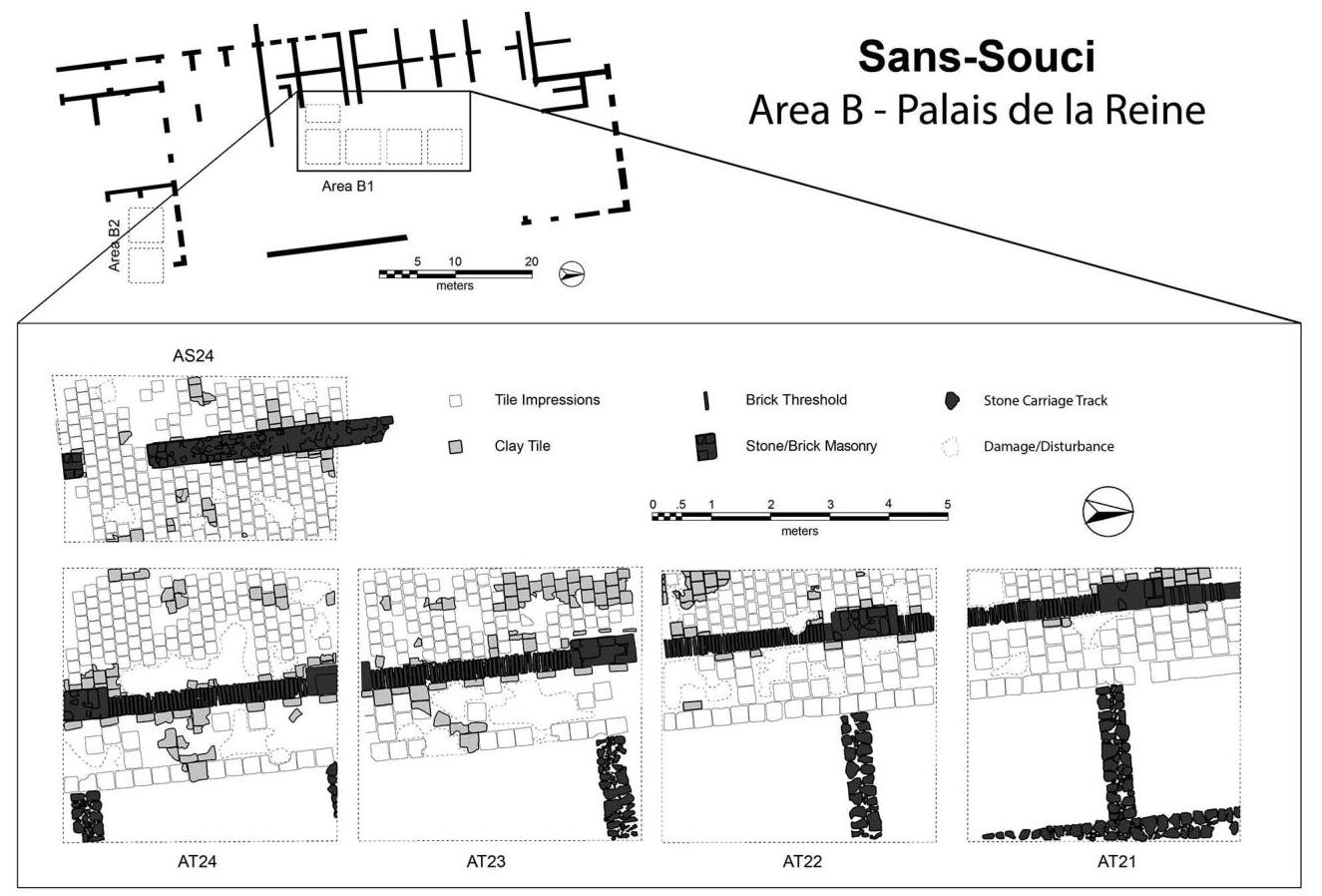

In 2017 we also opened new excavations in the so-called palais de la reine (designated area B) to test the suggestion that this building was contemporary to the EPB in area A and possibly Christophe’s original palace on the site. Excavations in one square (AS24) revealed a small section of the building’s interior. Excavations across three squares (AS24, AT24, and AT23), however, revealed the piers of an exterior arcade, connected by a brick threshold that extended along the east side of the palais de la reine (fig. 7). Overall, this layout confirms Karl Ritter’s visual representation of the building, published in 1836, which shows three arches granting entrance to this arcade. Additionally, our excavations revealed the remains of a clay tile and mortar floor that extended across both the arcade and the building’s interior, as well as out onto a patio to the east. Excavating through the floor material of the arcade and exterior patio, we discovered a second wall foundation. This foundation rests just to the east of the brick arcade threshold and associated stone piers, and the two features diverge by 1.5 degrees. This foundation thus represents an earlier structure, one possibly torn down during the construction of the palais de la reine. In 2018, we extended excavations in two units to the north (squares AT21 and AT22), revealing a

Figure 6. Views of MAP excavations in the Palais des Ministres, area A2. Left, View of the platform identified under room 10 (taken from the south). Right, View of the stone and brick staircase discovered under room 11 (taken from the south).

Figure 7. Plan of MAP excavations in the Palais de la Reine, area B1, showing arcade threshold and piers, clay tile floors throughout the structure, and carriage tracks extending south from an exterior patio.

Figure 8. Views of MAP excavations in the Palais de la Reine, area B1. Left, View of a wall foundation in squares AT21 and AT22 situated below the exterior patio of the royal era building (from the north). Right, View of earlier phase construction in square AT22 extending under the exterior patio and carriage tracks of the royal era building (from the east). Note the natural rocky surface at the bottom of both excavation units.

nearly identical stratigraphic sequence. In square AT22 our excavations identified another earlier structure of unknown function positioned in alignment with the foundation described above (fig. 8).

This earlier foundation was dug into a layer of construction fill composed of a mix of soil, stone, broken brick, fragmented roof tiles, both clay and white marble tiles, and a range of artifact types that extended across all units. The assemblage of artifacts recovered in this layer was essentially identical to that collected in the Christophe-era midden of area A, yet the high frequency of fragmentary structural debris suggests an existing building was torn down nearby in the process of leveling the area. Fragments of the same diagnostic pearlware with even scalloped edges and impressed straight lines identified in the midden of area A were also recovered in this fill. Therefore, the fill upon which both buildings in area B were constructed must date after 1805. Thus the palais de la reine itself cannot have been constructed at the same time as the EPB in area A; however, this earlier structure identified very well may have been. Vergniaud Leconte wrote that Christophe’s first building was, in fact, located on the site of the palais de la reine (Leconte 1931:338), and it is possible that we have identified the “superb home” described by Norbert Thoret (Nouët, Nicollier, and Nicollier 2013:47). All of this is to say that in a decade of construction, Christophe managed to refashion the landscape at Sans-Souci at least three times, suggesting an evolution and expansion of the use of these architectural tools of power over time and drawing from an overall plan that was already well established.

Domestic Assemblages

The artifact assemblages recovered from these contexts allow us to begin to characterize the material aspects of everyday life at Sans-Souci in the period between the revolution and the royal era (1805-1810). Excavations in areas A and B have recovered over 14,000 artifacts, including iron, ceramic, glass, animal bone, copper, lead, and stone objects. The domestic material recovered in middens and construction fills of areas A and B can thus tell us quite a bit about international trade, local production, and cultural traditions in the years between the revolution and the commencement of monumental building activity at Sans-Souci in 1810.

The quantity and diversity of imported ceramics in this assemblage is notable, particularly given the numerous trade embargoes forced on Haiti in the years after 1804 (fig. 9). One interesting aspect of the ceramic assemblage is the presence of large numbers of late eighteenth-century French faience and lead-glazed earthenwares, which make up approximately 30% of the assemblage. It is possible that sets of French pottery were collected from old colonial sites and reused at Sans-Souci. Such reclamation strategies are readily acknowledged in reference to military hardware and artillery, specifically French cannons (Rocourt 2009:149). Additionally, during the construction of the Citadelle, General Christophe commanded one colonel to organize farm laborers to disassemble bricks from abandoned plantations across the Plaine du Nord (Bailey 2017:73). Such sites were seen as assemblages of resources that could be reused within the new polity, and it is not inconceivable that

Figure 9. Ceramic artifacts from MAP excavations at Sans-Souci. Left, Domestic pottery. A−B, lead-glazed earthenware; C D, stoneware; E−G, French faience (tin-glazed earthenware); H−I, English creamware; J−M, English pearlware; N−P, wheel-thrown unglazed coarse earthenware; Q−T, handmade Afro-Caribbean ware. Right, Locally produced decorated tobacco pipes with short geometric stems.

quotidian objects such as tablewares were also strategically collected from French Plantation sites, possibly from Habitation Milot itself.

Additionally, however, refined English wares are visible also in the assemblage. Small quantities of English creamwares and pearlwares stand out ( 14% of the assemblage). Similarly, ongoing analysis of the industrially produced coarse wares ( 18% of the assemblage) suggests that 72% are of a type manufactured in London (Jillian Galle, personal communication, 2018). Haiti actively sought to expand trade with Great Britain via Jamaican ports in this period, and Julia Gaffield (2015) has described an extensive clandestine trade with port colonies such as Curaçao and St. Thomas. The English pottery excavated in both areas A and B seems to attest to such trading opportunities. Overall, the assemblage largely lacks matching sets and is quite heterogeneous, supporting the notion that these items arrived on palace grounds through either opportunistic or clandestine means. However, this early evidence of a preference for English material culture stands as an important precedent for efforts to expand trade with England during Christophe’s reign as King.

However, locally produced ceramics with clear AfroCaribbean inspirations have been identified in our excavations. For one, the assemblage contained a number of locally produced tobacco pipes (fig. 9). Tobacco pipes produced in England or Holland were typically made with diagnostic kaolin clay that fires bright white, and approximately 71% of the pipes recovered fit into this category. The remainder, however, were made in local brown clays and were characterized by forms not encountered in European examples. These pipes were

also heavily decorated with stamps and thin lines of punctate incisions. A number of these pipes were shaped in faceted geometric forms, and all were of the short stem variety. Shortstemmed pipes are commonly found in contact period West African contexts and occasionally recovered Afro-Caribbean sites (Handler 1983; Monroe 2002; Ozanne 1964), indicating the survival of African inspired smoking traditions in postrevolutionary Haiti. Additionally, large numbers of handmade, lowfired, grit-tempered, globular cooking vessels with scalloped shoulder decorations were recovered in both areas ( 34% of the ceramic vessel assemblage) (fig. 9Q-T). These pots are similar in every way to African-derived potting traditions across the Caribbean and strongly suggest an Afro-Caribbean source for cooking traditions at Sans-Souci. Despite the large-scale adoption of “European taste” in the architectural and artifactual records, potting and pipe making represent clear evidence for local, African-inspired traditions at Sans-Souci in its early years of occupation after the revolution.

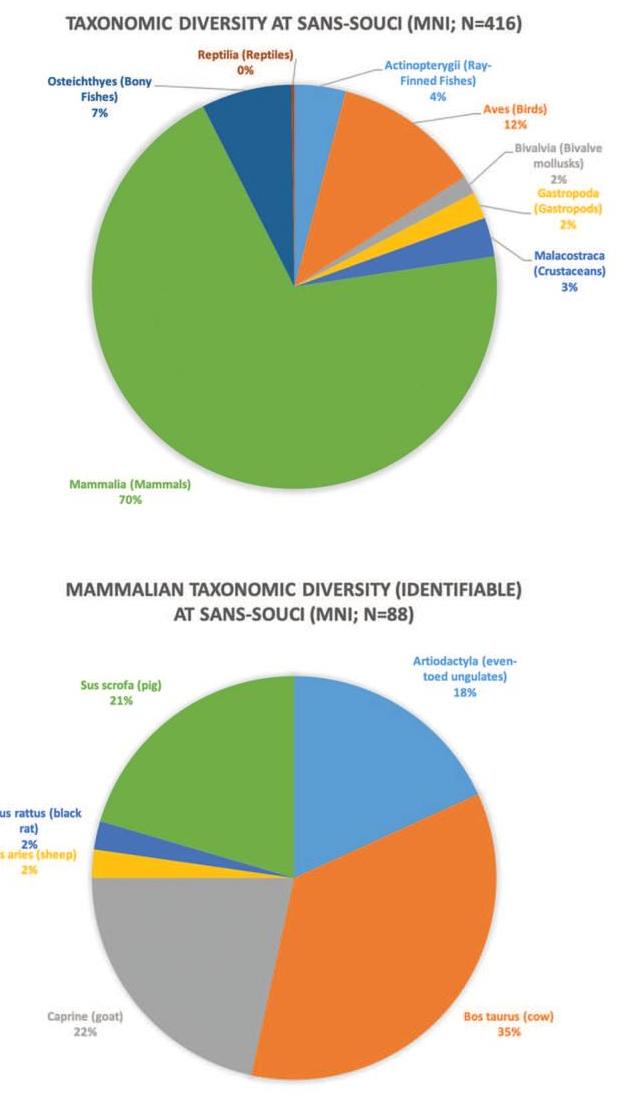

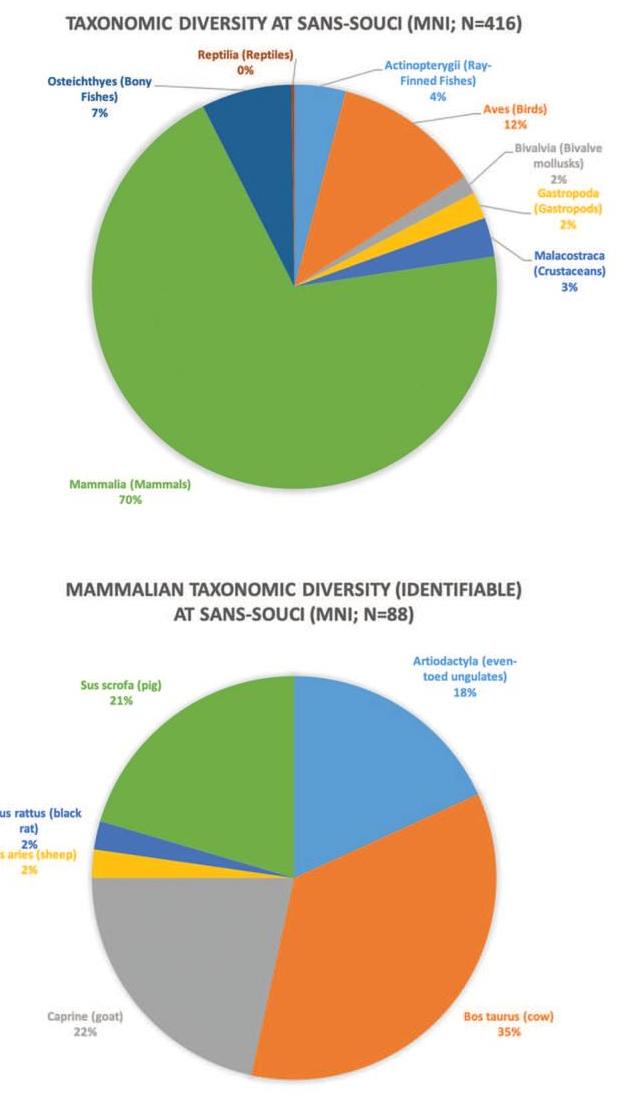

While the style of these cooking vessels is suggestive, even more important is what went into them. Archaeologists have noted that faunal assemblages associated with the African diaspora are characterized by high rates of chop marks and overall fragmentation, representing a diet based largely on stews, as well as much greater species diversity, including a prevalence of wild fauna (Franklin 2001; Heinrich 2012; McKee 1999). Our excavations have recovered nearly 1,300 animal bone fragments, of which 463 specimens recovered in the midden in area A were identified by David Ingleman (Ingleman 2015; Monroe 2017). This faunal assemblage suggests that site occupants drew from a broad faunal resource base (fig. 10). The

Figure 10. Top, Taxonomic diversity of identifiable faunal specimens. Right, Taxonomic diversity of identifiable mammalian specimens.

assemblage is dominated by barnyard animals (cow, goat, pig, and chicken). However, smaller quantities of wild terrestrial fauna and marine resources (including marine fish and mollusks) are also represented. Additionally, the mammalian faunal assemblage includes both forelimbs, hind limbs, and axial elements, indicating that at least a portion of the domesticates were locally raised and butchered. Cut marks were identified on 11.5% of the mammal bone specimens and 6% of the avian assemblage, a pattern consistent with culinary practices in which meat was chopped and prepared in stews rather than sawed and roasted over an open flame. The high-quality meals prepared at Sans-Souci, therefore, were prepared in ways that had deep cultural roots in Afro-Caribbean cuisine.

Conclusions

The archaeology of slavery in the Atlantic world has expanded its intellectual terrain substantially in recent decades. Once

restricted to questions of cultural continuity and creolization on plantations of the American South, archaeologists are now exploring political, economic, and cultural entanglements on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as the material lives that Africans and African-Americans built after slavery. The archaeology of slavery has thus adopted a truly global perspective that is yielding a new understanding of the formation of the colonial world and its lasting legacies. Although the quest for individual freedom and personal sovereignty have emerged as central themes in new research agenda, scholars have rarely examined the new political formations that took root in the wake of emancipation. Haiti, oft-cited exemplar of state making in the ashes of colonial slavery, is particularly well situated to answer important questions about the materiality of sovereignty seeking in the past.

In this paper, I have emphasized that sovereignty depends fundamentally on establishing firm control over territories, building international affiliations and alliances, and establishing novel forms of status distinction among audiences of subjects. The aforementioned discussion of historical and architectural evidence from the Kingdom of Haiti provides a new appreciation of the complex intersections of culture, politics, and economics in the decades following the Haitian Revolution. Monumental architecture and luxury goods were adopted to send targeted messages to subjects and sovereigns alike. Buildings were a central component of strategies to embrace the Enlightenment ideology of universal liberty. At SansSouci, this ideology was most clearly materialized in the incorporation of neoclassical facades and architectural elements, the symbolic currency of the day for expressing universal liberty and cultural modernity. At the same time, however, the massive scale of the site sent clear messages of royal power and status distinction to Haitian citizens across the kingdom. Architecture served as an active agent in the production of political sovereignty in Haiti. This new Haitian elite sought to fill their domestic spaces with material culture manufactured in Europe, reflecting a set of consumer practices embraced universally by mercantile elites living around the Atlantic world. Imported wealth, sequestered behind palace walls, thereby served to accentuate social distance between ruler and the ruled. Neoclassical architectural motifs, and imported material culture, were thereby domesticated to serve decidedly Haitian political agendas.

Importantly, these practices can be traced back to the intervening years between the end of the revolution (1804) to the transition to monarchy in Christophe’s Haiti (1811), suggesting an evolution and expansion of the use of these material symbols as tools of power over time. Indeed, ongoing archaeological research at Sans-Souci, which builds on previous work by Haitian authorities, has identified multiple layers of occupation extending back to the contact era, including two phases of occupation that date between the revolution and the royal era (1805-1810). Excavations within middens dating to this period have revealed large quantities of imported items from France and, to a lesser degree, Great Britain. This

material reflects the complex networks of exchange upon which Christophe depended to acquire imported material culture but may also reveal initial efforts by Christophe to establish mercantile connections with Great Britain. However, just as Christophe was beginning to experiment with material symbols of power deployed by communities across the Atlantic world, Afro-Caribbean cultural practices continued unabated within domestic contexts, providing salient reminders of the African roots of this experiment in political independence. Indeed, the preparation of wild and domestic fauna, cooked in Afro-Caribbean vessels and served on French and English plates, represents the emergence of an Afro-creole diet at SansSouci, one that speaks to a deeply rooted Afro-Caribbean cultural transcript unfolding in Haiti after the revolution.

Sovereignty in the Kingdom of Haiti thus represents a form of creolization at the political scale, providing a new vista from which to appreciate the nature of political movements in the Age of Revolutions. However, a number of key questions remain. Does the presence of older French pottery in this earlier phase reflect a pattern whereby Christophe reintroduced colonial material culture into his cupboards? Does the large-scale discard of this material represent a pattern of “cleaning house” as his later complex was built, and what do the corresponding domestic assemblages look like? Does the large quantity of locally produced tobacco pipes and handmade Afro-Caribbean wares speak to an expansion of local economic networks? Would these cultural traditions be rejected in later years, following the construction of the neoclassical palace façade? There is clearly much more work to be done to answer these and other questions to our fullest ability. What is clear, however, is the extent to which Christophe’s court creatively assembled European and Afro-Caribbean material traditions to assert their claims to Haitian sovereignty in the years after the Haitian Revolution.

Acknowledgments

The research upon which this article is based would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of numerous individuals and agencies. Officials from the Bureau National Ethnologie (Directeur Général Erol Josué and Jerry Michel), the Institut Sauvegarde du Patrimoine National (Directeur Général Jean-Patrick Durandis, Elsoit Colas, Neat Achille, and Eddy Lubin), and the Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien (Directeur Général Michelle Frisch and Camille Louis), and others (Monique Rocourt and Frederick Mangones) provided the authorizations, logistical support, and archival materials necessary for launching and sustaining this research project. Multiple individuals have contributed their time and effort to support four seasons of fieldwork (Rebecca Davis, Daphne Dorcé, Christopher Grant, David Ingleman, Marc Joseph, Camille Louis, Gabriela Martinez-Rocourt, Christine Markussen, Shayla Monroe, Katie Simon, and Junior Théodore), to analyze the artifactual (Danielle Dadiego, Jillian Galle) and faunal (David Ingleman) remains, to do community outreach

(Alexandra Jones), and to provide assistance with historical sources (Paul Clammer, Marlene Daut, Julia Gaffield). Our hosts at the Lakou Lakay Cultural Center (Maurice and Innocent Etienne) sustain us throughout our fieldwork each year. I am also forever grateful to the men and women of Milot who work with us on site, as well as the broader community of Milot for welcoming us each year. Last, I thank the Wenner-Gren Foundation, and Ibrahima Thiaw and Deborah L. Mack, for organizing the stimulating seminar in which this paper was presented, and I also thank the seminar participants and anonymous reviewers for providing valuable comments on its earlier draft. This research was funded by the UC Santa Cruz Office of Research, the Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies, the Wenner-Gren Foundation, the National Geographic Society, and the National Science Foundation (1916728).

References Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo sacer: sovereign power and bare life. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Agnew, John A. 2018. Globalization and sovereignty: beyond the territorial trap. 2nd edition. Lanham, MD: Rowan & Littlefield.

Alpern, Stanley B. 1998. Amazons of black Sparta: the women warriors of Dahomey. New York: New York University Press.

Ardouin, Beasbrun. 1858. Etudes sur l’histoire d’Haiti. Paris.

Armstrong, Douglas V. 2003. Creole transformation from slavery to freedom: historical archaeology of the East End community, St. John, Virgin Islands. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Armstrong, Douglas V., and Mark Fleishman. 2003. House-yard burials of enslaved laborers in eighteenth-century Jamaica. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 7(1):33-65.

Armstrong, Douglas V., and Elizabeth Jean Reitz. 1990. The old village and the great house: an archaeological and historical examination of Drax Hall Plantation, St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica. Blacks in the New World. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Ashmore, Wendy. 1989. Construction and cosmology: politics and ideology in lowland Maya settlement patterns. In Word and image in Maya culture: explorations in language, writing, and representation. W. F. Hanks and D. S. Rice, eds. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

-1 1991. Site-planning principles and concepts of directionality among the Ancient Maya. Latin American Antiquity 2(3):199-226.

Ashmore, Wendy, and Bernard Knapp. 1999. Archaeologies of landscape. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bailey, Gauvin Alexander. 2017. Der Palast von Sans-Souci in Milot, Haiti (ca. 1806-1813): das vergessene Potsdam im Regenwald [The palace of SansSouci in Milot, Haiti (ca. 1806-1813): the untold story of the Potsdam of the rainforest]. Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag.

2018. Architecture and urbanism in the French Atlantic Empire state, church, and society, 1604-1830. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Battle-Baptiste, Whitney. 2011. Black feminist archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast.

Bentmann, Reinhard, and Michael Müller. 1992. The villa as hegemonic architecture. London: Humanities.

Blackmore, Chelsea. 2014. Commoner identity in an ancient Maya village: class, status, and ritual at the Northeast Group, Chan, Belize. British Archaeology Reports. Oxford: Archeopress.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a theory of practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

-1 1990. The logic of practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

-2 2003. The Berber house. In The anthropology of space and place: locating culture. S. M. Low and D. Lawrence-Ziitiga, eds. Pp. 131-141. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Brinchmann, Knute, Eddy Lubin, Giselle Hyvert, and Herold Gaspard. 1985. Sans Souci: 1984 and 1985. Report submitted to the Institut de Sauvegarde du Patrimoine National, Haiti. Cap-Haitien, Haiti.

Brown, J. 1837. The history and present condition of St. Domingo. Philadelphia: W. Marshall.

Brumfiel, Elizabeth M. 1991. Weaving and cooking: women’s production in Aztec Mexico. In Engendering archaeology: women and prehistory. J. M. Gero and M. W. Conkey, eds. Pp. 224-252. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

-1 1992. Distinguished lecture in archaeology: breaking and entering the ecosystem-gender, class, and faction steal the show. American Anthropologist 94(3):551-567.

Calvert, Karin. 1994. The function of fashion in eighteenth-century America. In Of consuming interests: the style of life in the eighteenth century. C. Carson, R. Hoffman, and P. Albert, eds. Pp. 252-283. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Carson, Cary. 1994. The consumer revolution in colonial British America: why demand? In Of consuming interests: the style of life in the eighteenth century. C. Carson, R. Hoffman, and P. Albert, eds. Pp. 483-697. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

-1997. Material culture history: the scholarship nobody knows. In The shape of the field. A. S. Martin and J. R. Garrison, eds. Pp. 417-420. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Casey, Edward S. 1997. The fate of place: a philosophical history. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cattelino, Jessica. 2010. The double bind of American Indian need-based sovereignty. Cultural Anthropology 25(2):235-262.

Cheesman, Clive, ed. 2007. The Armorial of Haiti: symbols of nobility in the reign of Henry Christophe. London: College of Arms.

Cole, Hubert. 1967. Christophe: King of Haiti. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

Congrove, Denis E. 1993. The Palladian landscape: geographical change and its cultural representation in sixteenth-century Italy. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

Costin, Cathy L. 1993. Textiles, women, and political economy in late Prehispanic Peru. Research in Economic Anthropology 14:3-28.

D’Altroy, Terence N., and Christine Ann Hastorf. 2001. Empire and domestic economy: interdisciplinary contributions to archaeology. New York: Kluwer Academic.

de Cauna, Jacques. 1990. Memoire des leux, liues de memoire: toponymie du Parc Historique National. Chemins Critiques 1(4):125-140.

-2004. Toussaint Louverture et l’indépendance d’Haiti: Témoignages pour un bicentenaire. Paris: Editions Karthala et Société Française d’Histoire d’Outre-Mer.

-2012. Toussaint Louverture: le grand précurseur. Bordeaux: Editions Sud-Ouest.

DeCorse, Christopher. 1999. Oceans apart: Africanist perspectives of diaspora archaeology. In I, too, am America: archaeological studies of AfricanAmerican life. T. Singleton, ed. Pp. 132-155. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Dertz, James. 1970. Archaeology as social science. American Anthropological Association Bulletins 3(3):115-125.

-1996. In small things forgotten: an archaeology of early American life. Expanded and revised edition. New York: Anchor/Doubleday.

Delle, James A. 1998. An archaeology of social space: analyzing coffee plantations in Jamaica’s Blue Mountains: contributions to global historical archaeology. New York: Plenum.

-1 1999. The landscapes of class negotiation on coffee plantations in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica: 1790-1850. Historical Archaeology 33(1):136138 .

Delle, James A., Mark W. Hauser, and Douglas V. Armstrong. 2011. Out of many, one people: the historical archaeology of colonial Jamaica: Caribbean archaeology and ethnohistory. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

DeMarrais, Elizabeth. 2014. Introduction: the archaeology of performance. World Archaeology 46(2):155-163.

Dietler, Michael, and Brian Hayden. 2001. Feasts: archaeological and ethnographic perspectives on food, politics, and power. Smithsonian Series in Archaeological Inquiry. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Donley-Reid, Linda W. 1990. A structuring structure: the Swahili house. In Domestic architecture and the use of space: an interdisciplinary crosscultural study. S. Kent, ed. Pp. 114-126. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dresser, Madge, and Andrew Hann, eds. 2013. Slavery and the British country house. Swindon: English Heritage.

Dubois, Laurent. 2012. Haiti: the aftershocks of history. 1st edition. New York: Holt.

Farnsworth, Paul. 2001. Island lives: historical archaeologies of the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Fennell, Christopher. 2011. Early African America: archaeological studies of significance and diversity. Journal of Archaeological Research 19(1):1-49.

Ferguson, Leland G. 1992. Uncommon ground: archaeology and early African America, 1850-1800. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Fick, Carolyn E. 1990. The making of Haiti: the Saint Domingue revolution from below. 1st edition. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1980. Power/kneezidge: selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. 1st American edition. New York: Pantheon.

-1 1995 (1977). Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. New York: Random House.

Franklin, Maria. 2001. The archaeological and symbolic dimensions of soul food: race, culture and Afro-Virginian identity. In Race and the archaeology of identity. C. Orser, ed. Pp. 88-107. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Fritz, John. 1986. Vijayanagara: authority and meaning of a South Indian imperial capital. American Anthropologist 88:44-45.

Gaffeld, Julia. 2015. Haitian connections in the Atlantic World: recognition after revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Garraway, Doris L. 2012. Empire of liberty, kingdom of civilization: Henry Christophe, Baron de Vastey, and the paradoxes of universalism in postrevolutionary Haiti. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 16(3):1-21.

Geertz, Clifford. 2004. What is a state if it is not a sovereign? reflections on politics in complicated places. Current Anthropology 45(5):577-593.

Geggus, David Patrick. 1983. Slave resistance studies and the Saint Domingue slave revolt: some preliminary considerations. Miami: Latin American and Caribbean Center, Florida International University.

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Handler, Jerome. 1983. An African pipe from a slave cemetery in Barbados, West Indies. In The archaeology of the clay tobacco pipe. VIII. America. P. Davey, ed. Pp. 245-254. Oxford: BAR International Series.

Handler, Jerome S., Frederick W. Lange, and Robert V. Riordan. 1978. Plantation slavery in Barbados: an archaeological and historical investigation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hastorf, Christine Ann. 1991. Gender, space, and food in prehistory. In Engendering archaeology: women and prehistory. J. M. Gero and M. W. Conkey, eds. Pp. 132-162. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Hauser, Mark. 2007. Between urban and rural: organization and distribution of local pottery in eighteenth-century Jamaica. In Archaeology of Atlantic Africa and the African diaspora. A. Ogundiran and T. Falola, eds. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

-2008. An archaeology of Black markets: local ceramics and economies in eighteenth-century Jamaica. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Heath, Barbara, and Amber Bennett. 2000. “The little Spots allow’d them”: the archaeological study of African-American yards. Historical Archaeology 34(2):38-55.

Heinrich, Adam R. 2012. Some comments on the archaeology of slave diets and importance of taphonomy to historical faunal analyses. Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 1(1):9-40.

Helms, Mary. 1999. Why Maya lords sat on jaguar thrones. In Material symbols: culture and economy in prehistory. J. E. Robb, ed. Pp. 56-69. Carbondale: Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Hobbes, Thomas. 1982 (1651). Leviathan. 4th edition. New York: Penguin Classics.

Ingleman, David. 2015. The vertebrate archaeofauna of Sans-Souci, Haiti. Unpublished report, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Inomata, Takeshi. 2006. Plazas, performers, and spectators: political theaters of the Classic Maya. Current Anthropology 47(5):805-842.

Inomata, Takeshi, and Lawrence S. Cohen. 2006. Archaeology of performance: theaters of power, community, and politics. Archaeology in Society Series. Lanham, MD: AltaMira.

James, C. L. R. 1938. The black Jacobins: Toussaint Louverture and the San Domingo Revolution. London: Secker & Warburg.

Kelly, Kenneth, and Benoit Bérard. 2014. Bitasion: archéologie des habitations/ plantations des Peittes Antilles. Leiden: Sidestone.

Kelly, Kenneth, and Diane Wallman. 2014. Foodways of enslaved laborers on French West Indian plantations (18th-19th century). Afriques 5. https:// doi.org/10.4000/afriques. 1608

Leconte, Vergniaud. 1931. Henri Christophe dans l’histoire d’Haiti. Paris: Berger-Levrault.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The production of space. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Leone, Mark P. 1984. Interpreting ideology in historical archaeology: using the rules of perspective in the William Paca Garden in Annapolis,

Maryland. In Images of the recent past. C. Orser, ed. Pp. 25-35. Berkeley, CA: AltaMira.

-2005. The archaeology of liberty in an American capital: excavations in Annapolis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Leone, Mark P., Parker B. Potter, and Paul A. Shackel. 1987. Toward a critical archaeology. Current Anthropology 28(3):283-302.

Li, Daryl. 2018. From exception to empire: sovereignty, carceral circulation, and the “Global War on Terror.” In Ethnographics of U.S. Empire. C. McGranahan and J. F. Collins, eds. Pp. 456-476. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Lightfoot, Kent G., Antoinette Martinez, and Ann M. Schiff. 1998. Daily practice and material culture in pluralistic social settings: an archaeological study of culture change and persistence from Fort Ross, California. American Antiquity 63(2):199-222.

Madiou, Thomas. 1989. Histoire d’Haiti. Port-au-Prince: Editions Henri Deschamps.

Manigat, Leslie François. 2007. Henry Christophe, Alexandre Pétion: en deux médaillons distincts: la politique d’éducation nationale du premier, la politique agraire du second. Série: Les petites classiques de l’histoire vivante d’Haiti. Port-au-Prince: Média-Texte.

Martin, Ann Smart. 1994. “Fashionable sugar dishes, latest fashion ware”: the creamware revolution in the eighteenth-century Chesapeake. In Historical archaeology of the Chesapeake. P. A. Shackel and B. Little, eds. Pp. 169-186. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

McAnany, Patricia. 2001. Cosmology and the institutionalization of hierarchy in the Maya region. In From leaders to rulers. J. Haas, ed. Pp. 125-148. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

McIntosh, Tabitha, and Gregory Pierrot. 2017. Capturing the likeness of Henry I of Haiti (1805-1822). Atlantic Studies 14(2):127-151.

McKee, Larry. 1992. The ideals and realities behind the design and use of 19th century Virginia slave cabins. In The art and mystery of historical archaeology: essays in honor of Jim Dietz. A. E. Yentsch and M. C. Beaudry, eds. Pp. 195-214. Boca Raton, FL: CRC.

-1999. Food supply and plantation social order: an archaeological perspective. In “I, too, am America”: archaeological studies of African American life. T. A. Singleton, ed. Pp. 218-239. Charlotteeville: University Press of Virginia.

Miller, George L., and Richard R. Hunter. 1990. English shell-edged earthenware: alias Leeds ware, alias feather edge. In The consumer revolution in 18th century English pottery: proceedings of the Wedgwood International Seminar, no. 35, pp. 107-136.

Monroe, J. Cameron. 2002. Negotiating African-American ethnicity in the seventeenth-century Chesapeake: colono tobacco pipes and the ethnic uses of style. Oxford: Archaeopress.

-2009. “In the belly of Dan”: landscape, power, and history in precolonial Dahomey. In Excavating the past: archaeological perspectives on Black Atlantic regional networks. Los Angeles: Clark Library, UCLA.

-2010. Power by design: architecture and politics in precolonial Dahomey. Journal of Social Archaeology 10(3):477-507.

-2014. The precolonial state in West Africa: building power in Dahomey. New York: Cambridge University Press.

-2017. New light from Haiti’s royal past: recent archaeological excavations in the Palace of Sans-Souci, Milet. Journal of Haitian Studies 23(2):5-31.

Monroe, J. Cameron, and Anneke Janzen. 2014. The Dahomean feast: royal women, private politics, and culinary practices in Atlantic West Africa. African Archaeological Review 31(2):299-337.

Monroe, J. Cameron, and Akin Ogundiran. 2012. The power and landscape in Atlantic West Africa. In Power and landscape in Atlantic West Africa: archaeological perspectives. J. Cameron Monroe and Akin Ogundiran, eds. Pp. 1-48. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Moore, Jerry D. 1996. Architecture and power in the ancient Andes: the archaeology of public buildings. New Studies in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moran, Charles. 1957. Black triumvirate: a study of Louverture, Descalines, Christophe-the men who made Haiti. 1st edition. New York: Exposition.

Mullins, Paul. 1999. Race and the genteel consumer: class and AfricanAmerican consumption, 1850-1930. Historical Archaeology 31(1):22-38.

Nouët, J.-C., C. Nicollier, and Y. Nicollier. 2013. La vie aventureuse de Norbert Thoret dit “L’Americain.” Paris: Editions du Port-au-Prince.

Ortner, Sherry B. 1984. Theory and anthropology since the sixties. Comparative Studies in Society and History 26(1):126-166.

Oranne, Paul. 1964. Tobacco pipes of Accra and Shai. Legon: University of Ghana.

Pauketat, Timothy R. 2001. Practice and history in archaeology: an emerging paradigm. In Contemporary archaeology. R. W. Preucel and S. A. Mrozowski, eds. Pp. 137-155. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Pearson, Michael Parker, and Colin Richards. 1994. Architecture and order: approaches to social space. New York: Routledge.

Pogue, Dennis T. 2001. The transformation of America: Georgian sensibility, capitalist conspiracy, or consumer revolution? Historical Archaeology 35(2):4157.

Rabinow, Paul. 2003. Ordonnance, discipline, regulation: some reflections on urbanism. In The anthropology of space and place: locating culture. S. M. Low and D. Lawrence-Zúñiga, eds. Pp. 353-362. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Raguet, Condy. 1811. Memoirs of Hayti, Letter XX. The Port Folio 5(1):408-418. Ritter, Karl. 1836. Naturhistorische Reise Nach der Westindischen Insel Hayti. Stuttgart: Hallberger.

Rocourt, Monique. 2009. La Citadelle Henry: Edition Haiti-Histoire ϕ Culture. Port-au-Prince: Logo Plus.

Roux, P. 1816. Almanac royal d’Hayti pour l’année. Cap-Henry (Cap-Haitien): P. Roux.

Rutherford, Danilyn. 2012. Laughing at Leviathan: sovereignty and audience in West Papua. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Samford, Patricia. 2007. Subfloor pits and the archaeology of slavery in colonial Virginia. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Shackel, Paul A., Paul R. Mullins, and Mark S. Warner. 1998. Annapolis pasts: historical archaeology in Annapolis, Maryland. 1st edition. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Singleton, Theresa A. 1990. The archaeology of the plantation South: a review of approaches and goals. Historical Archaeology 24(2):70-77.

-1995. The archaeology of the African diaspora in the Americas. Glassboro, NJ: Society for Historical Archaeology.

-1999. I, too, am America: archaeological studies of African-American life. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

-2015. Nineteenth-century built landscape of plantation slavery in comparative perspective. In The archaeology of slavery: a comparative approach to captivity and coercion. L. Marshall, ed. Pp. 93-115. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Smith, Adam T. 2001. The limitations of Doxa. Journal of Social Archaeology 1(2):155-171.

-2003. The political landscape: constellations of authority in early complex polities. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

-2011. Archaeologies of sovereignty. Annual Review of Anthropology 40:415-432.

-2015. The political machine: assembling sovereignty in the Bronze Age Caucasus. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Thomas, Brian. 1998. Power and community: the archaeology of slavery at the Hermitage Plantation. American Antiquity 63(4):531-551.

Thornton, John. 1993. “I am the subject of the King of Congo”: African political ideology and the Haitian Revolution. Journal of World History 4(2):181-214.

Thrift, Nigel. 2004. Intensities of feeling: towards a spatial politics of affect. Human Geography 86(1):57-78.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1990. Haiti, state against nation: the origins and legacy of Duvalierism. New York: Monthly Review.

-1995. Silencing the past: power and the production of history. Boston: Beacon.

Vastey, Pompée Valentin. 1923. An essay on the causes of the revolution and civil wars of Hayti, being a sequel to the political remarks upon certain French publications and journals concerning Hayti. Exeter: Western Luminary Office.

Wilkie, Laurie A. 1997. Secret and sacred: contextualizing the artifacts of African-American magic and religion. Historical Archaeology 31(4):81106.

Wilkie, Laurie A., and Kevin M. Bartoy. 2000. A critical archaeology revisited. Current Anthropology 41(5):747-777.

Wilkie, Laurie A., and Paul Farnsworth. 2005. Sampling many pots: an archaeology of memory and tradition at a Bahamian plantation. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Yentsch, Anne E. 1990. Minimum vessel lists as evidence of change in folk and courtly manners of food use. Historical Archaeology 24(3):24-53.

-1991. Chesapeake artefacts and their cultural context: pottery and the food domain. Post-Medieval Archaeology 25:25-72.

-1994. A Chesapeake family and their slaves: a study in historical archaeology. New Studies in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

J. Cameron Monroe

J. Cameron Monroe